The German publisher "De Gruyter" will publish my book "The Visionary Academy of Ocular Mentality / Atlas of the Iconic Turn" in 2020.

For copright issues, the texts and portraits have been deleted from my site.

https://www.degruyter.com/view/title/576202?rskey=YrMB7X&result=6

"The Visionary Academy of Ocular Mentality" (brilliant title suggested to me by the great philosopher Arthur C. Danto) is a pictorial iconography of contemporary philosophy, art criticism, art theory, cultural history,literature, antropology, a "collective" project.

The participants / contributors to the book and project are among the most important philosophers, art historians, art critics and theorists such as Arthur Danto, WJT Mitchell, Horst Bredekamp, Thomas Crow, David Carrier, Mieke Bal, Griselda Pollock, Joseph Leo Koerner, TJ Clark, Hans Belting, Richard Brettell, David Freedberg, Salvatore Settis, Gottfried Boehm, Michael Ann Holly, Keith Moxey,Andreas Beyer, Harold Bloom, Norman Bryson, Daniel Dennett, James Clifford, Jacques Ranciere, Jean-Luc Nancy, Marc Augé, George Steiner, Samuel Delany, David Summers, Martin Kemp, Stephen Bann, Peter Burke, Stephen Greenblatt, Alexander Nemerov, Judith Butler, Nancy Fraser, Simon Critchley,Donna Haraway, Thomas Macho, Gary Schwartz, Barry Schwabsky, John Yau, Jonathan Crary, Andreas Huyssen, Michel Onfray, Jerry Fodor, ect.

https://hyperallergic.com/507133/confronting-art-critics-with-their-own-portraits/

"Critical Theory in and of the Flesh "

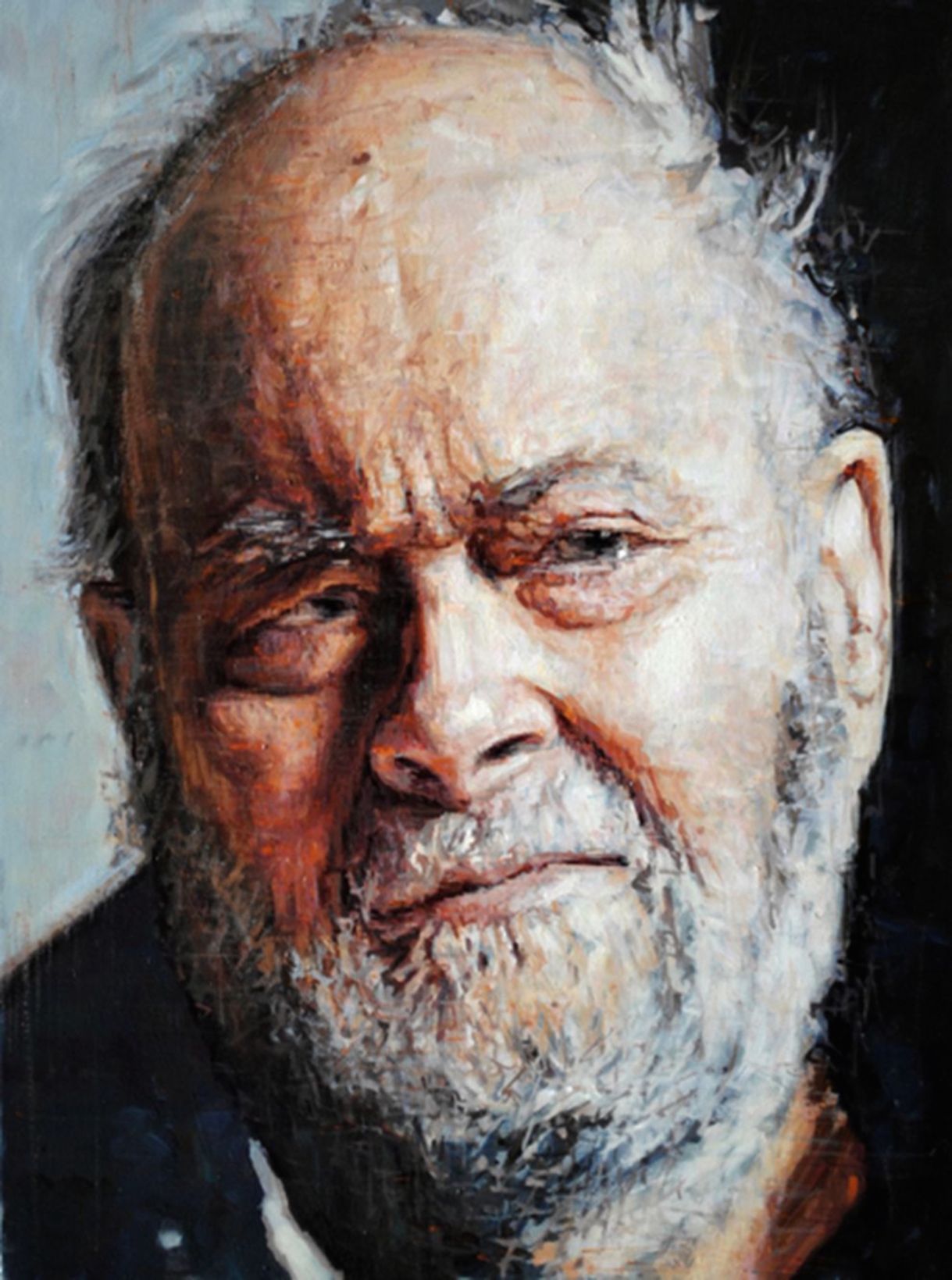

In Luca Del Baldo’s portrait of me, I see a face, which is recognizably mine, but which confronts me through an extended series of mediations. It is me, to be sure, but me as refracted through the eyes (and hands) of several others. The first and most important other is Del Baldo himself, who materializes his seeing of me through paint on canvas. But he has never laid eyes on me in the flesh. He has painted me, rather, from a photograph. It is one that I sent him myself, as an email attachment, after selecting it from the file of “publicity shots” stored on my computer. The photograph was taken by another other, Uwe Dettmar, who did meet me face-to-face, but whose work was shaped by institutional imperatives. Dettmar was engaged to produce my likeness for the homepage of the Humanities Research Center in Bad Homburg Germany, which wished to advertise its then-current crop of Fellows, of which I was one. From this photograph, Del Baldo produced a “me” that amalgamates disparate agendas and ways of seeing, not least his own. It certainly is a likeness of me–and a very good one at that. But the “me” that appears on his canvas incorporates traces of a larger social world. And that world is quite complex. Comprising individuals, institutions and social relations, it is shot through with orders of normative and aesthetic value, with structures of political economy and power asymmetry. I have no doubt that Del Baldo is interested in, indeed playing with, the complexities of representation, He is concerned, it seems to me, with the relation between seeing and thinking. In titling his project “The Visionary Academy of Ocular Mentality,” he explicitly juxtaposes two registers: on the one hand, the corporeal subject whose visible likeness he creates, a subject with a body and a face, who occupies a specific location in space and time; on the other, the thought that subject germinates, which strives for a disembodied existence that transcends its context of origin. The result is a striking revelation: philosophical reflection issues from embodied individuals. Its transcendence is grounded in immanence. Mind wears a sensuous face. Interestingly, this entanglement of immanence and transcendence is central to the philosophical tradition with which I identify. For Critical Theory, thought necessarily arises from specific historical contexts, which mark it in ways that often escape notice. Often, too, the marking is a kind of warping, which prettifies domination and excuses injustice, even despite good intentions. Exposing such ideological distortion is one of the tasks of Critical Theory, which works in part by excavating the buried threads that tie thought to the social worlds that simultaneously enable and constrain it. But there’s a catch. Critique cannot exempt itself from the suspicion it casts upon others. Cultivating historical self-awareness, it must do its best, which will never be good enough, to guard against its own contamination by the built-in biases of its situation. With respect to itself, then, as well as to others, Critical Theory insists on philosophy’s immanence, its inescapable entanglement with the here-and-now. But there is also another aspect of Critical Theory. Unwilling to abide exclusively in the realm of suspicion, this tradition also affirms transcendence. Rejecting a view of “the given” as a static, unchanging prison, it seeks out the small shoots and tendrils which, although tethered to the earth, reach out to the sun. In this second register, critique gives voice to hope by disclosing possibilities for emancipation. The possibilities it seeks are not abstract, ideal, or out-of-time, however, not the sort that invite escapism. On the contrary, they are historical possibilities, which emerge from within a social situation that is itself self-contradictory and dynamic. In disclosing those possibilities, Critical Theory links the desire for transcendence with the aspiration to overcome domination, while grounding those impulses historically, in a social reality that moves. Much more could (and should!) be said about Critical Theory’s distinctive approach to the co-imbrication of immanence and transcendence. Here, however, I want only to signal its resonance with Del Baldo’s problematic of “Ocular Mentality.” There too one encounters the peculiar entanglement of soaring thought with fleshly immanence. As I contemplate his portrait of me, however, I struggle to hold those two poles together– because now they are poles of me. I am a philosopher who aspires to clarify the impasses of her time in hopes of discerning a path that leads beyond them. But I am also an embodied natural being with a face. This face is mine alone, but it also speaks volumes about our social world in accents that should be legible to Critical Theory. It is the face of a human animal, white, European-descended, gendered female, middle-aged but healthy looking, reasonably well preserved, and groomed in ways that bespeak nutritional and medical advantages born of the privileges of class, color, and national citizenship. I am flesh, but in my flesh is written an entire history of domination on a global scale. And in reading my flesh, I find my philosophical voice as a Critical Theorist. Seeking to decode the given, I also hope to transcend it. In the fleshly immanence of present-day social reality I search for signs that point beyond it.© Nancy Fraser

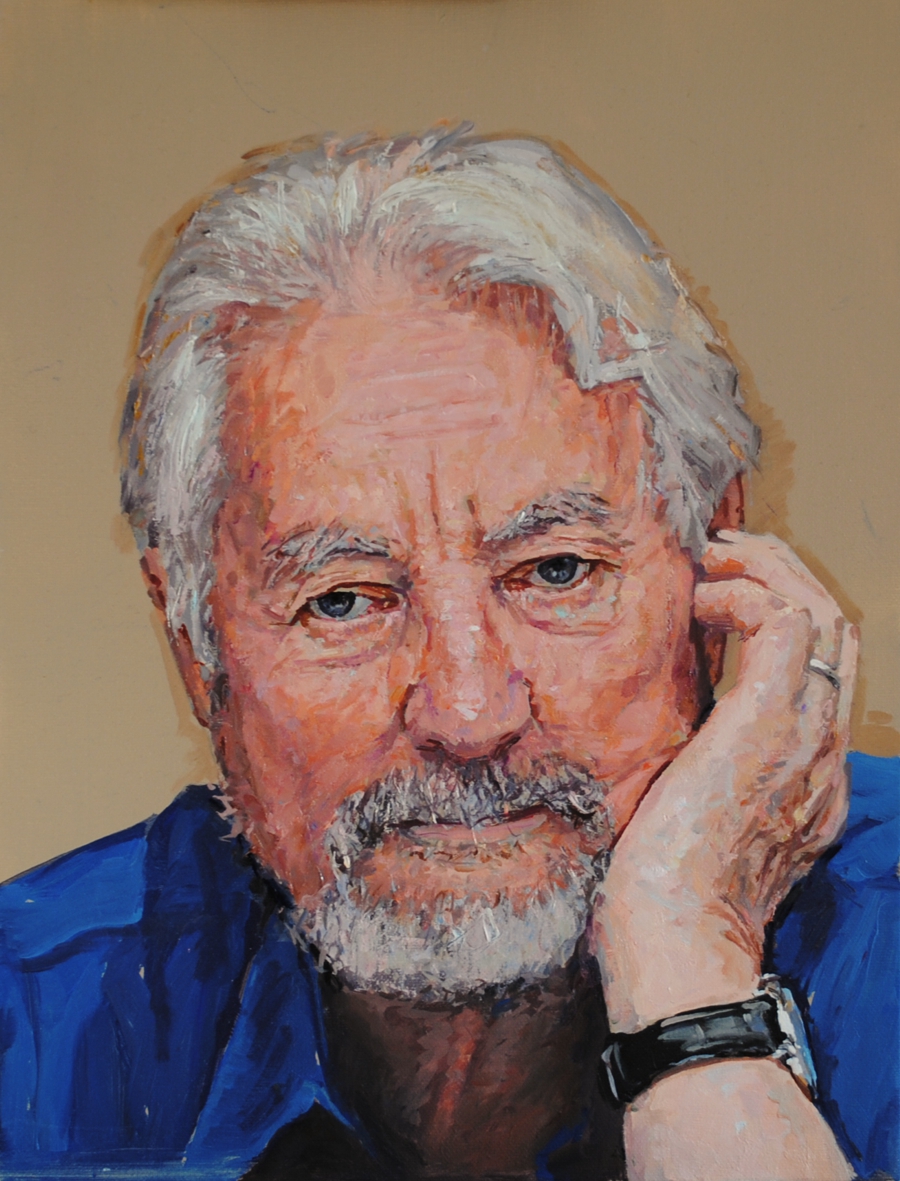

Portraits teach us much about those who directly, or indirectly, have impacted our lives. Families everywhere treasure paintings, photographs, or silhouette cut-outs depicting relatives and ancestors whose names have been lost in the mists of time, because they provide visual connections to our roots and personal histories. Portraits of family members often spark memories, adding new dimensions to stories that are already important to the fabric of our lives. In the most fundamental sense, Luca Del Baldo is enriching the family heritage of everyone he invited to participate in his “collective” portrait series, for each of us will receive the painting he made on the basis of a photograph sent to him. In my case, the connections to family are many since my daughter-in-law, KK Ottesen, was the photographer, and I am standing in the courtyard of the National Gallery of Art, where I served as curator for 45 years. While portraits are of great interest for families, they also provide remarkable windows into worlds far beyond our own domestic spheres. We often turn to portraits to understand the distant past. When I think of ancient Egypt, for example, I not only reflect on the great pyramids, but also on the timeless images of pharaohs honed from black granite or other unyielding materials. I can trace my captivation with Egypt to my childhood when I first encountered the exotic face of Queen Nefertiti in my grandfather’s study, for a reproduction of the famed bust of the Egyptian queen sat on his large writing desk. Another portrait that played a role in connecting me to the past is Hans Holbein’s iconic portrayal of King Henry VIII. Henry’s power and might are unmistakable, both because of his elaborate wardrobe and the way his bulky mass fills the picture plane. Holbein’s image was never far from in my mind when studying English history or when reading Hilary Mantel’s Wolf Hall. How different is that perception of leadership from the one Kehinde Wiley created with a far more approachable portrait of Barack Obama, who sits quietly and reflectively against a backdrop of greenery and flowers. 2 Artist self-portraits are another source of constant interest, for they offer insights into how their makers presented themselves to society. For example, Peter Paul Rubens never portrayed himself as a practicing artist. On the contrary, he showed himself as a debonair aristocrat comfortable with humanists and royalty, his primary patrons. Rubens, who always dressed appropriately for his high social status, invariably wore a wide-brimmed hat to hide his receding hairline. Without any reservation, he adhered to Renaissance ideals of proper decorum expressed by Baldassare Castiglione in his influential manual, The Book of the Courtier. A very different artist image emerges from Rembrandt’s many painted, drawn, and etched self-portraits. We see him in all aspects of his life, and in many guises. Rembrandt appears as a young aspiring artist in Leiden, then as a towering master in Amsterdam until, late in life, his body, if not his indominable spirit, began to weaken and fail. He showed himself as a beggar sitting on a mound of dung, a respectable burgher, an artist holding his brushes and palette, but also in costumes that evoked Renaissance scholars and exotic travelers from abroad. Rembrandt, however, never idealized his own features, and, over time, we see his bulbous nose widen and his jowly cheeks grow ever more distended. The one constant is his steady gaze, often heavy and not without sadness. In a number of self-portraits, Rembrandt left his eyes partially obscured in shadow, allowing us to find our own path into the window of his soul. In similar ways, the personas and personal histories of other artists become ever more understandable through their self-portraits, not least among them Vincent van Gogh. Portraits of thinkers whose ideas have helped shape the course of human history are also endlessly intriguing. Portrait series of important ancient philosophers, writers and artists often hung in the studies of Renaissance and Baroque humanists. Images of Aristotle, Plato and Socrates, imaginative or real, still spark our interest because they help ground the abstract ideas 3 of these philosophers into physical realities to which we can all connect. The same can be said for Lucas Cranach’s depictions of the pugnacious Marten Luther, or Albrecht Dürer’s engraving of Erasmus thoughtfully writing at a desk in his study. Dürer’s engraving helped spread Erasmus’ fame throughout Europe, much as do photographs and videos of twentieth-century leaders and thinkers, such as Martin Luther King, Jr. We look at portraits because they help connect us with others, providing some sense of their physical appearance and psychological character, but we also enjoy portraits because they are often beautiful and compelling works of art. Many questions exist, however, about the art of portraiture, not least the nature of the relationship between artist and sitter. What message is being conveyed through pose, costume, pictorial setting, chiaroscuro effects, or degree of finish? How does an artist suggest the sitter’s inner life? What about a painting’s scale? What difference does it make if a portrait can be worn on a necklace, is displayed in a grand entrance hall, or published in a book? Does it matter if an artist paints or draws directly from a living model or from an intermediary image, such as an antique cameo, engraving or photograph, a pictorial source that nineteenth century artists, among them Thomas Sully and Thomas Eakins, began using after the invention of photography? Luca Del Baldo’s project —to publish a “collective” portrait of individuals involved in the arts, literature and philosophy, with accompanying written commentaries — raises a number of fascinating questions. Unlike traditional portrait series, Luca had little or no role in selecting the photographs. Hence, his distinctive manner of painting, not the figure’s pose or setting, is the visual link that connects these images. Although his portraits essentially remain true to the sitter’s appearance, faces appear somewhat craggier than in reality because of his distinctive manner of modeling with bold, unblended brush strokes. As befitting a portrait series featuring 4 writers and thinkers, he emphasizes eyes, for they purportedly allow access to the sitter’s inner being. It should be noted, however, that Luca’s portraits are not the essence of the project, only its byproduct. The portraits will never be exhibited together as a group, as Luca is sending each sitter his or her portrait for their own private enjoyment. Luca’s “collective” portrait is a revolutionary concept that merges painting, photography, and written texts in ways that will yield fascinating insights into the nature of philosophical and art historical discourse in the late twentieth- and early twenty-first centuries.

© Arthur K. Wheelock Jr

© Marc Augé

"For Luca del Baldo"

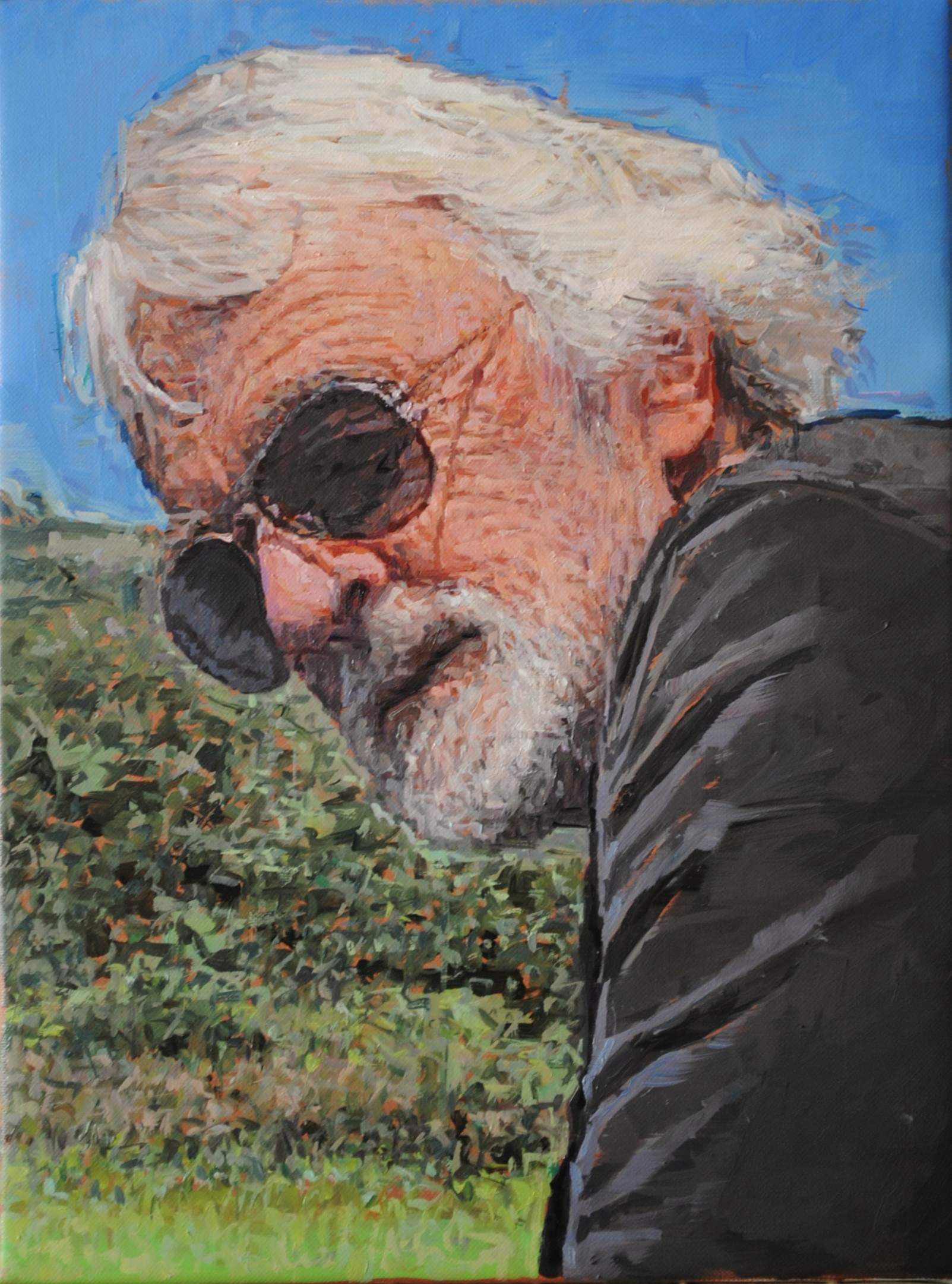

What is it they say? – ‘Every picture tells a story.’ Or maybe it cannot itself tell the story, and waits patiently to hear one told about it, true or false – waits for the proud old proprietor to turn aside in the corridor and say: ‘They say the lady in the painting belonged to a family with lands above Trento, and she came down to Bergamo in search of a husband, and when she was twenty-two or twenty-three, alas…’ My story does not have an unhappy ending. The photograph I sent Luca del Baldo was taken two or three years ago, in a place I love: a great sweep of hills and forest by the Pacific, with whales going by, and paths where you can walk for an hour and see no one. For twenty years it was where I walked with my wife at weekends. It is very far away now, and I miss it, and we go back from time to time. The photo shows me sitting in the sunshine. I remember I was planted on a great fallen branch of a tree – the shadows of still living branches are visible on the grass. The tree stands above a stream running down to the beach – the Pacific is a few hundred yards away. I think the tree is a cottonwood. It is a massive, isolated, feathery thing; a landmark; you come over the hills from inland and see it below you against the ocean. I understand why Luca chose to edit the photograph I sent him, cutting away the right-hand third and concentrating on the creases on my face. The whole photo is (as they say) ‘too anecdotal’. As I was sitting on the whitened branch, a crow flew down from the cottonwood and perched on the branch close beside me. We held our breath. The bird sat still. I heard my wife reaching for her i-phone – I think the slight atmosphere of worry about my face must be partly me hoping the moment would last long enough to be recorded. It did. The crow was an entirely benign presence – both of us who saw it that morning had no doubt of that. It was welcoming me back to a land I cared for. If its blackness had a tinge of mortality to it – and I suppose that even in the charmed moment there must have been a faint sense of that in the background – it was as tactful, as gentle, as reasonable a harbinger as anyone could wish for. We were in America, but not the America of Poe. I know my face has its fill of wrinkles, and maybe my mouth looks a bit sour and skeptical. But these are superficial, or anyway banal. It is Baudelaire who asks somewhere (I’m quoting from memory, and probably making him too sunny): ‘Qui n’a pas connu l’un de ces beaux jours de l’esprit…?’ – a day when air and color flood in as never before, and time stops, and all the world is a Delacroix. Let my face – absurdly, counter-factually, I concede – be the face of such a moment. There is one more thread to the story. I said that often while walking the hills my wife and I were more or less alone, but earlier that morning we’d rounded a bend and come face to face with someone we knew well – someone we’d lost touch with, and never really expected to see again. She had been one of our students. One of the best: she ended up writing a wonderful study of Mayakovsky and Rodchenko. I say she was one of the best; but she had not been one of the happiest. I believe – the matter was never talked about explicitly – that something dreadful, something violent, had been done to her in the past. She was courageous and humane: I know she spent years as a valued counselor in a Rape Crisis Center. So you can imagine what it meant to us to see her accompanied on the path by a beautiful small boy, whom she introduced as her son. His name, she said, was Zephyr. They were returning from a night in a campsite by the ocean. Please then, when you look at my portrait, see me still basking in life’s occasional good luck.

© T.J. Clark